Sylvia Plath in her journals

One of Ted Hughes’s most important books is his edition of the Collected Poems of Sylvia Plath, published in 1981. There are few precedents - only Mary Shelley springs immediately to mind - for a creative artist taking on the academic role of textual editor of their dead spouse’s works.

A combination of personal knowledge and patient scholarship enabled Hughes to arrange Plath’s poems in chronological order. To the chagrin of some feminists, he took it upon himself to relegate her early work to the status of “juvenilia”, beginning the run of her mature poems in 1956 - the year of their now legendary first encounter at a Cambridge gathering of student poets.

By Hughes’s reckoning, Plath wrote 224 poems between 1956 and her suicide at the age of thirty in the freezing February of 1963. He argued that her breakthrough into that uniqueness of voice which constitutes poetic greatness came with the seven-part sequence “Poem for a Birthday”, composed in late 1959 while the two were in residence at Yaddo, the artists’ retreat in upstate New York. The title of Hughes’s collection of elegiac autobiographical poems, Birthday Letters (1998), is, among other things, a tribute to this moment in Plath’s career.

from “Poem for a Birthday”

Hitherto, her poems had been highly accomplished but somehow brittle. A self-description in a journal entry of late 1955 is harsh but apt: “Roget’s trollop, parading words and tossing off bravado for an audience.” Too much reliance on the thesaurus, that is to say. Very few poems written before Yaddo haunt the reader; almost all the hundred or so thereafter sear themselves into our consciousness. Years earlier, Plath had dreamed of “gathering forces into a tight tense ball for the artistic leap”. At Yaddo, she made that leap.

On 10 October 1959, she wrote in her journal: “Feel oddly barren. My sickness is when words draw in their horns and the physical world refuses to be ordered, recreated, arranged and selected. When will I break into a new line of poetry? Feel trite.” And on the thirteenth: “Very depressed today. Unable to write a thing. Menacing gods. I feel outcast on a cold star”. But then on the twenty-second, walking in the woods in the frosty morning light, she found the “Ambitious seeds of a long poem made up of separate sections: Poem on her Birthday. To be a dwelling on madhouse, nature. The superb identity, selfhood of things. To be honest with what I know and have known. To be true to my own weirdnesses.”

Within a fortnight the sequence was “miraculously” written. What was it that released the flow? Hughes pointed to the influence of the poetry of Theodore Roethke, but the entry of 19 October offers a wealth of other clues. Plath records there that she has written two poems that “please” her, “one a poem to Nicholas, and one the old father-worship subject”: one to the father who had died when she was eight, the other to the unborn child in her womb - for whom a boy’s name has been chosen (although it turned out to be a girl, Frieda; Nicholas was born just over two years later). She was about eighteen weeks pregnant. Did the baby quicken and give its first kick at this time? That earlier phrase “oddly barren” becomes explicable as the journals turn to a sense of new life.

There is also confidence in her husband: “Ted is the ideal, the one possible person.” Yet in the same entry we find the following: “Involvement with [the novelist] Mavis Gallant. Her novel on a daughter-mother relation, the daughter committing suicide.” Plath goes on to make her own plans for a novel. Everything comes together: father, mother, husband, unborn child, new poetic voice, prospective novel about a girl’s suicide attempt (which would become The Bell Jar). During the previous months, Plath has been in psychoanalysis, describing her mother as “a walking vampire”, exploring her own “Electra complex” and wondering “how to express anger creatively”. Back in 1956, a week after meeting Hughes, she had confided to her journal: “I would live a life of conflict, of balancing children, sonnets, love and dirty dishes.” With the venting of the anger against her parents and the kick of the child in the womb, the balancing act could begin. Out of it came great art.

An extract from Mavis Gallant’s novel Green Water, Green Sky was published in the New Yorker in June 1959

Plath’s journals were first published, under the aegis of Hughes, in 1982. That edition was incomplete. There were extensive cuts, and two volumes, from August 1957 to November 1959, were excluded. It was Hughes’s intention to keep them sealed until the fiftieth anniversary of Plath’s death. Reading the matricidal notes from the time of her psychoanalysis, one can see why.

Shortly before his own death, Hughes changed his mind, as part of that same process of release and reparation which led to the publication of Birthday Letters and the writing of Alcestis (a small masterpiece of simultaneous translation and autobiography). So it is that the surviving journals were published in full in 2000, meticulously edited and annotated by Karen V. Kukil, keeper of the Plath archive at her alma mater, Smith College in Massachusetts.

Two further bound volumes, covering Plath’s final three years, remain lost. One of them may yet conceivably turn up, but the other - which ran up to within three days of Plath’s suicide - was destroyed by Hughes. We will never know what she wrote about the process of composing her extraordinary last poems (“The woman is perfected. / Her dead / Body wears the smile of accomplishment”).

Reading the complete Journals of Sylvia Plath 1850-1962 we discover that she was a much better prose writer than Hughes gave her credit for: he frowned on her stories, smeared as they were with the garish lipstick of Mademoiselle magazine. The woman writing privately in her diaries, but perhaps in the knowledge that, should she achieve her ambition of literary success they might one day be published, can be feisty and funny as well as maudlin and self-indulgent.

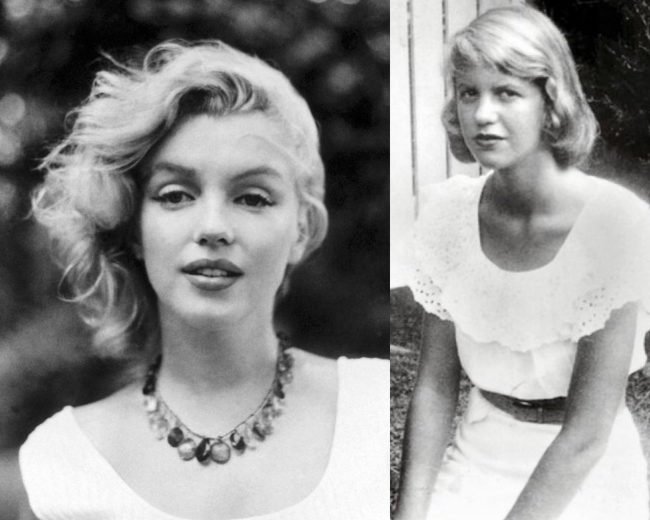

Inevitably, though, her death casts its shadow back on entries long before - not only the portentous (“I desire the things which will destroy me in the end”), but also, more poignantly, the superficially inconsequential (“Marilyn Monroe appeared to me last night in a dream as a kind of fairy godmother”).

Plath and her “fairy godmother”

The greater the artist, the more we will want to explore that complex alchemy whereby experience is transmuted into imaginative creation. Entries such as those made at Yaddo in October 1959 offer revelation after revelation about Plath’s discovery that art could be made from truth to her own “weirdnesses”. To an even greater extent than her letters, now published in two weighty volumes, the journals take the reader into the consciousness of this brilliant woman who was so damaged by her experiences of her father’s death and her depression:

All my life I have been “stood up” emotionally by the people I loved most: daddy dying and leaving me, mother somehow not there.

I am so close to the dark. My villanelle was to my father; and the best one. I lust for the knowing of him; I looked at [Theodore] Redpath [one of her tutors] at that wonderful coffee session at the Anchor [student pub in Cambridge], and practically ripped him up to beg him to be my father; to live with the rich, chastened, wide mind of an older man. I must beware, beware, of marrying for that.

Her brio as a prose writer reveals itself not only in her self-awareness (“I am at my best in illogical sensuous description”), but also in her literary-critical intelligence. To end, here she is on Virginia Woolf and D. H. Lawrence, writers to whom I will turn in future posts:

How does Woolf do it? How does Lawrence do it? I come down to learn of those two: Lawrence, because of the rich physical passion – fields of force – and the real presence of leaves and earth and beasts and weathers, sap-rich, and Woolf because of that almost sexless, neurotic luminousness – the catching of objects: chairs, tables & the figures on a street corner, and the infusion of radiance: a shimmer of the plasm that is life.

But to become her true writerly self, she adds, “I cannot & must not copy either.”

This post is expanded and adapted from my original review of Karen Kukil’s superb edition of Plath’s unabridged journals