Anna Akhmatova revisited

“Poetry is respected only in this country,’’ wrote Osip Mandelstam, “people are killed for it. There’s no place where more people are killed for it.’’ In modern America, where poetry struggles even to retain its place in the school curriculum, it is singularly instructive to hear such voices from Soviet Russia. Especially at a time when once again Russian tyranny is rearing its head and bringing death, destruction and misery to thousands. Doubly so, in the weeks after a brave Ukrainian poet (and novelist), Victoria Amelina, lost her life to a missile strike on a shopping center in Kramatorsk. As a group of young Russian writers are kowtowing to Putin and celebrating the war in so-called Z-Poetry, we need to be reminded that throughout the Soviet era poets were leading voices of resistance. Where in today’s Russia is a Mandelstam or a Joseph Brodsky? Are they silenced, exiled, or cunningly writing poems beyond the visibility of the tyrannical state regime?

Not knowing the answer to that question, this summer’s news of the killing of Victora Amelina sent me not only to her work, but also back to Anna Akhmatova, one of the essential poets of the twentieth century, who still, to my mind, remains insufficiently known in the English-speaking world. This post is a revisiting and expansion of something I wrote about her nearly twenty years ago on the publication of the best possible English-language introduction to her life and work, a beautifully produced volume edited by the scholar Nancy K. Anderson under the title The Word that causes Death’s Defeat: Poems of Memory. It offers a concise and compelling biography, elegant and accessible translations of Akhmatova’s three most significant long poems, and a highly informative critical commentary.

“She was not born Anna Akhmatova,” Anderson reminds us, “She came into the world on June 11, 1889, as Anna Andreyevna Gorenko, the daughter of a naval officer.’’ When Anna was 17, it came to her father’s attention that she had the unladylike ambition of becoming a poet. He warned her not to bring shame to his name; she replied that she didn’t need his name, “and promptly disowned the entire masculine side of her lineage by choosing as her literary name the maiden name of her maternal grandmother’’.

As Anderson says, this was a creative choice as well as a splendidly rebellious one. Anna Gorenko somehow lacks the resonance of Anna Akhmatova, a name that her contemporary Marina Tsvetayeva compared to “a great sigh / Falling into a depth without name’’. Lovers and husbands would follow father in telling Anna what to do, but she would carry on going her own way.

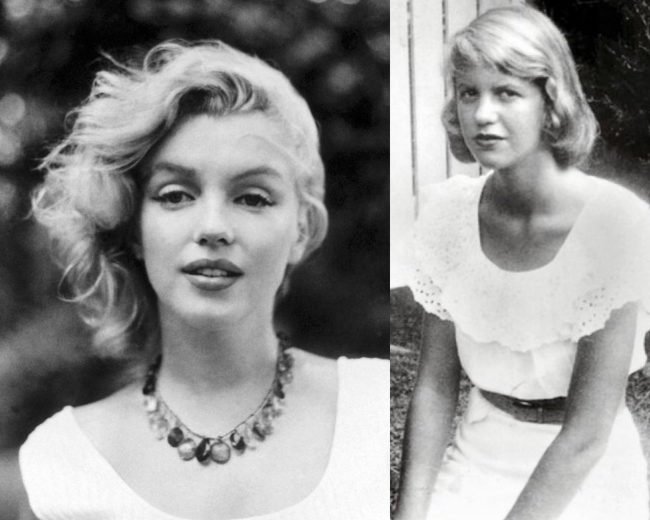

She was a young woman of extraordinary beauty and charisma. A poet called Nikolai Gumilyov, who had first met her when she was out shopping for Christmas tree ornaments as a 14-year-old girl, courted her for six years – with several suicide attempts along the way – before she finally agreed to marry him. They had a tempestuous open marriage and hung out at a Petersburg cafe called the Stray Dog where, together with Mandelstam, they developed a new school of poetry called Acmeism.

Acmeism offered a finely honed alternative to the noisier new school of the time, Futurism, a movement associated with the flamboyant Vladimir Mayakovsky, who is nicely described by Anderson as “a sort of Russian anticipation of the Beat poets’’.

Akhmatova’s peculiar gift was to combine two diametrically opposed styles in the same poet: she is at once understated and passionate, classical and romantic, matter-of-fact and radiant. To find a comparison from English poetry of the same vintage, you would have to imagine some strange alchemical combination of hot-blooded D. H. Lawrence and Edward Thomas, quietest of the war poets.

Akhmatova is without English peer not only for style but also for subject-matter: she was a major poet of both world wars, of the Bolshevik revolution and the end of Tsarist Russia, of the civil war and above all of Stalin’s terror. In August 1921 she looked at a copy of Pravda posted on the wall of a railway station. It announced that 61 counter-revolutionaries had been summarily executed. Among them was her estranged first husband Gumilyov. “A garment of new grief I made, I sewed it for my love. / Oh Russian earth, it loves the taste, it loves the taste of blood.’’

Her own poems were denounced as reactionary. The Soviet party line was that her work represented a hangover from the era of Tsarist elitism; she failed to address the proletariat, only concerning herself with free love and religion. Half-nun and half-whore, she was born too late and had failed to die in time.

As Stalin’s grip tightened, her friend and fellow-poet Mandelstam spoke out. She was in his apartment when the knock came at midnight. Mandelstam had composed – but sensibly not written down – some verses about Stalin himself: “His cockroach whispers leer / And his boot tops gleam... And every killing is a treat / For the broad-chested Ossete.’’ He would eventually die in a transit camp.

Akhmatova’s son was arrested by the NKVD for, among other supposed counter-revolutionary activities, reciting this poem. Anna interceded with Stalin on his behalf and gained a temporary reprieve, but the boy was re-arrested and eventually sent to the gulag. Anna spent a year and a half on the “prison lines’’, the queues of wives and mothers waiting for news of their loved ones.

This was the experience that inspired her greatest poem sequence Requiem – included in the Anderson volume. Again, it was a poem too dangerous to be written down. Instead it was learned by heart and only committed to print during the thaw of the Khrushchev years.

Akhmatova went on to experience the siege of Leningrad. Her powerful and enigmatic Poem without a Hero – published posthumously and fully translated in the Anderson volume – grew from this wartime trauma. It was then in 1945 that she had her famous meeting with Isaiah Berlin, whom she called “the guest from the future.” Her own future was mixed: a period of post-war poetic stagnation, a campaign to get her son released from his ten-year sentence in a Siberian prison camp, and at last an element of international recognition and internal rehabilitation. Then, shortly before her death in 1966, publication of her final long poem, The Way of all the Earth (which completes the triptych of major works in Anderson’s book). Her sorrowful words live on in the darkness of our time: “What’s left of old Europe, / Is only a scrap, / In its smoke-shrouded cities / Fire and death reign …” But at the end, there is a glimmer of the hope for peace that the art of poetry has the unique power to put into words. Akhmatova writes of how she

Journeys alone,

Without brother, or friend,

Or the man I loved first,

Bearing only a pine branch

And one sunlit verse

Dropped by a beggar

And picked up by me …

In my last dwelling place

May I find peace.

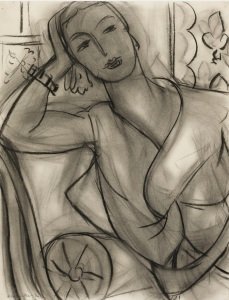

Akhmatova in 1922, portrait by Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin (public domain)

To emend …

… or not to emend? That is the perennial question for Shakespearean editors.

… or not to emend? That is the perennial question for the Shakespearean editor. I recently received a message from an avid reader of our edition of the Complete Works, asking whether there was an error in the third line of the following stanza in our text of Venus and Adonis:

They pointed out that all the other editions they had consulted read ‘prey’ instead of ‘pray’. The simile of feeding on prey would seem to fit better with the hunting imagery that pervades the poem (which is about hunter and hunted), and would be consistent with the overt image of a bird of prey in the previous stanza:

My initial instinct, in the haste of other work, was to check the definitive Arden edition of Shakespeare’s Poems and, yes, it reads ‘prey’ and there is no textual note suggesting that this is an emendation of the original 1593 First Quarto of Venus and Adonis. The Arden editors simply annotate prey with ‘See 55-8n’, a cross-reference to the note to the previous stanza, which glosses ‘sharp by fast’, ‘tires’ (‘tears flesh in feeding’), and ‘gorge be stuffed’ as imagery associated with birds and beasts of prey. So I capitulated, confessed to an error, thanked my eagle-eyed reader, and promised to correct in the next reprint.

But a nagging doubt remained: how could this error have crept into the text? When we prepared the RSC edition, I edited the narrative poems and sonnets, but I worked closely with associate editor Jan Sewell, and the text was checked by Eric Rasmussen, our even more eagle-eyed General Editor with primary responsibility for text—checked, too, by a very good copy editor and proof readers in both the UK and the USA. So I went to the original text, in order to compare lines 58 and 63:

‘Pray’ in both stanzas. Mystery solved? Because ‘prey’ was sometimes spelt ‘pray’ in Shakespeare’s time, and because the context in line 58 is definitely that of a bird of prey, editors modernize the spelling to ‘prey’. This is what we did in line 58. Our apparent mistake was not to follow other editors in also modernizing the spelling in line 63. What, then, were we thinking of? At this point, somewhat belatedly, I turned to our own edition and saw that we had provided a very different explanatory note from that in the Arden:

63 pray prayer (puns on ‘prey’)

Then I remembered the rationale. The Oxford English Dictionary gives us the original (now obsolete) meaning of pray as a noun:

Look again at the context: yes, the imagery in the previous stanza is of hunting, but in this one it is of holiness: ‘heavenly moisture’, ‘air of grace’, not to mention those ‘distilling showers’ that are like dewdrops from Heaven in a psalm or prayer. The breath of Adonis is being compared to a prayer.

The prey/pray pun signals a shift from Venus thinking ‘I want to devour you (sexually)’ to a thought along the lines of ‘even though I am the goddess, you are a divine boy whose very breath is holy, giving of grace and life’—perhaps also ‘I want you to want me, I want you to be praying to make love to me instead of chasing that old boar’. It is a move that beautifully captures the double nature of desire—one part lustful rapacity, the other loving transcendence—that is so very much theme of the poem.

So we will not be emending in the next reprint of our edition. If there is any dereliction of editorial duty, it is to be found in those editions that do not alert readers to the pun. In our justification of our editorial procedures in creating the RSC edition, we cited the advice of that great editor and critic Dr Samuel Johnson, who wrote in the preface to his edition:

“To alter is more easy than to explain, and temerity is a more common quality than diligence … I have adopted the Roman sentiment, that it is more honourable to save a citizen, than to kill an enemy, and have been more careful to protect than to attack.”

I believe that we were right to explain, indeed to save, ‘pray’ rather than have the temerity to change it to ‘prey’. In short, on the matter of emendation, when in doubt, don’t. Or, if the reading in the original text is defensible, then retain it.

Sylvia Plath in her journals

One of Ted Hughes’s most important books is his edition of the Collected Poems of Sylvia Plath, published in 1981. There are few precedents - only Mary Shelley springs immediately to mind - for a creative artist taking on the academic role of textual editor of their dead spouse’s works.

A combination of personal knowledge and patient scholarship enabled Hughes to arrange Plath’s poems in chronological order. To the chagrin of some feminists, he took it upon himself to relegate her early work to the status of “juvenilia”, beginning the run of her mature poems in 1956 - the year of their now legendary first encounter at a Cambridge gathering of student poets.

By Hughes’s reckoning, Plath wrote 224 poems between 1956 and her suicide at the age of thirty in the freezing February of 1963. He argued that her breakthrough into that uniqueness of voice which constitutes poetic greatness came with the seven-part sequence “Poem for a Birthday”, composed in late 1959 while the two were in residence at Yaddo, the artists’ retreat in upstate New York. The title of Hughes’s collection of elegiac autobiographical poems, Birthday Letters (1998), is, among other things, a tribute to this moment in Plath’s career.

from “Poem for a Birthday”

Hitherto, her poems had been highly accomplished but somehow brittle. A self-description in a journal entry of late 1955 is harsh but apt: “Roget’s trollop, parading words and tossing off bravado for an audience.” Too much reliance on the thesaurus, that is to say. Very few poems written before Yaddo haunt the reader; almost all the hundred or so thereafter sear themselves into our consciousness. Years earlier, Plath had dreamed of “gathering forces into a tight tense ball for the artistic leap”. At Yaddo, she made that leap.

On 10 October 1959, she wrote in her journal: “Feel oddly barren. My sickness is when words draw in their horns and the physical world refuses to be ordered, recreated, arranged and selected. When will I break into a new line of poetry? Feel trite.” And on the thirteenth: “Very depressed today. Unable to write a thing. Menacing gods. I feel outcast on a cold star”. But then on the twenty-second, walking in the woods in the frosty morning light, she found the “Ambitious seeds of a long poem made up of separate sections: Poem on her Birthday. To be a dwelling on madhouse, nature. The superb identity, selfhood of things. To be honest with what I know and have known. To be true to my own weirdnesses.”

Within a fortnight the sequence was “miraculously” written. What was it that released the flow? Hughes pointed to the influence of the poetry of Theodore Roethke, but the entry of 19 October offers a wealth of other clues. Plath records there that she has written two poems that “please” her, “one a poem to Nicholas, and one the old father-worship subject”: one to the father who had died when she was eight, the other to the unborn child in her womb - for whom a boy’s name has been chosen (although it turned out to be a girl, Frieda; Nicholas was born just over two years later). She was about eighteen weeks pregnant. Did the baby quicken and give its first kick at this time? That earlier phrase “oddly barren” becomes explicable as the journals turn to a sense of new life.

There is also confidence in her husband: “Ted is the ideal, the one possible person.” Yet in the same entry we find the following: “Involvement with [the novelist] Mavis Gallant. Her novel on a daughter-mother relation, the daughter committing suicide.” Plath goes on to make her own plans for a novel. Everything comes together: father, mother, husband, unborn child, new poetic voice, prospective novel about a girl’s suicide attempt (which would become The Bell Jar). During the previous months, Plath has been in psychoanalysis, describing her mother as “a walking vampire”, exploring her own “Electra complex” and wondering “how to express anger creatively”. Back in 1956, a week after meeting Hughes, she had confided to her journal: “I would live a life of conflict, of balancing children, sonnets, love and dirty dishes.” With the venting of the anger against her parents and the kick of the child in the womb, the balancing act could begin. Out of it came great art.

An extract from Mavis Gallant’s novel Green Water, Green Sky was published in the New Yorker in June 1959

Plath’s journals were first published, under the aegis of Hughes, in 1982. That edition was incomplete. There were extensive cuts, and two volumes, from August 1957 to November 1959, were excluded. It was Hughes’s intention to keep them sealed until the fiftieth anniversary of Plath’s death. Reading the matricidal notes from the time of her psychoanalysis, one can see why.

Shortly before his own death, Hughes changed his mind, as part of that same process of release and reparation which led to the publication of Birthday Letters and the writing of Alcestis (a small masterpiece of simultaneous translation and autobiography). So it is that the surviving journals were published in full in 2000, meticulously edited and annotated by Karen V. Kukil, keeper of the Plath archive at her alma mater, Smith College in Massachusetts.

Two further bound volumes, covering Plath’s final three years, remain lost. One of them may yet conceivably turn up, but the other - which ran up to within three days of Plath’s suicide - was destroyed by Hughes. We will never know what she wrote about the process of composing her extraordinary last poems (“The woman is perfected. / Her dead / Body wears the smile of accomplishment”).

Reading the complete Journals of Sylvia Plath 1850-1962 we discover that she was a much better prose writer than Hughes gave her credit for: he frowned on her stories, smeared as they were with the garish lipstick of Mademoiselle magazine. The woman writing privately in her diaries, but perhaps in the knowledge that, should she achieve her ambition of literary success they might one day be published, can be feisty and funny as well as maudlin and self-indulgent.

Inevitably, though, her death casts its shadow back on entries long before - not only the portentous (“I desire the things which will destroy me in the end”), but also, more poignantly, the superficially inconsequential (“Marilyn Monroe appeared to me last night in a dream as a kind of fairy godmother”).

Plath and her “fairy godmother”

The greater the artist, the more we will want to explore that complex alchemy whereby experience is transmuted into imaginative creation. Entries such as those made at Yaddo in October 1959 offer revelation after revelation about Plath’s discovery that art could be made from truth to her own “weirdnesses”. To an even greater extent than her letters, now published in two weighty volumes, the journals take the reader into the consciousness of this brilliant woman who was so damaged by her experiences of her father’s death and her depression:

All my life I have been “stood up” emotionally by the people I loved most: daddy dying and leaving me, mother somehow not there.

I am so close to the dark. My villanelle was to my father; and the best one. I lust for the knowing of him; I looked at [Theodore] Redpath [one of her tutors] at that wonderful coffee session at the Anchor [student pub in Cambridge], and practically ripped him up to beg him to be my father; to live with the rich, chastened, wide mind of an older man. I must beware, beware, of marrying for that.

Her brio as a prose writer reveals itself not only in her self-awareness (“I am at my best in illogical sensuous description”), but also in her literary-critical intelligence. To end, here she is on Virginia Woolf and D. H. Lawrence, writers to whom I will turn in future posts:

How does Woolf do it? How does Lawrence do it? I come down to learn of those two: Lawrence, because of the rich physical passion – fields of force – and the real presence of leaves and earth and beasts and weathers, sap-rich, and Woolf because of that almost sexless, neurotic luminousness – the catching of objects: chairs, tables & the figures on a street corner, and the infusion of radiance: a shimmer of the plasm that is life.

But to become her true writerly self, she adds, “I cannot & must not copy either.”

This post is expanded and adapted from my original review of Karen Kukil’s superb edition of Plath’s unabridged journals

Aldous Huxley

Huxley’s encounter with mescaline - dictaphone running, to record the effects - was the most celebrated act of English literary drug-taking since Thomas De Quincey gulped down his laudanum.

There is a neat Sheryl Crow song about a hippie chick that begins “She was born in November 1963 / The day that” - and you think she is going to sing “Kennedy died”, but it actually goes “Aldous Huxley died.” It was, as a matter of fact, the same day. Huxley finds his place in a rock song of the Nineties because he was one of the godfathers of the psychedelic experimentation of the Sixties. Indeed, the very word “psychedelic” was coined in correspondence between him and a psychiatrist called Humphry Osmond, who shared his fascination with hallucinogenic drugs.

Huxley’s encounter with mescaline - dictaphone running, to record the effects - was the most celebrated act of English literary drug-taking since Thomas De Quincey gulped down his laudanum. Huxley went on to write a book about his drug-induced hallucinations entitled The Doors of Perception thus providing a name for the archetypal rock band of the era, Jim Morrison’s The Doors.

The irony of Huxley’s becoming a guru of the hedonistic age of recreational drugs is that back in the early 1930s he had written his great anti-utopia, Brave New World, in which he warns against a world where a brainwashed populace pop happy pills instead of achieving true intellectual liberation by reading Shakespeare. In seeking nirvana through mescaline and LSD, he was forgetting his own greatest achievement: Ecstasy, the pill, test-tube babies, Virtual Reality, rampant consumerism, the leisure industry - all are prophesied by this extraordinary novel.

When George Orwell wrote Nineteen Eighty-Four at the beginning of the Cold War, he sent a copy to Huxley, who replied that he had enjoyed it but that he thought his own book was a better prophecy. The future would bring not Orwell’s famous image of a repressive state boot smashing down on a human face, but a brave new world of advertising and mind-control in which the people are made to “love their servitude”.

In the battle of the futurologists, Orwell took the lead with his anatomy of Communist oppression, but as we move into the world of CRISPR gene-editing technology and VR pornography, Huxley does indeed look more prophetic.

But Aldous Huxley was far more than the author of Brave New World. He was the kind of all-round public intellectual - novelist, satirist, upmarket journalist, science writer, social commentator, essayist ranging across all the arts - whom we associate more with continental than English life. His life was a mirror of the 20th century. Being the grandson of the populariser of evolutionary theory, T. H. Huxley (“Darwin’s bulldog”), he began with an acute consciousness of the intellectual advances of the previous century, near the end of which he was born.

Then during the First World War, in which he did not serve because of his appalling eyesight (an infection in youth left him almost blind), he became a member of Lady Ottoline Morrell’s Garsington set. This precipitated him into the world of Bloomsbury. He was thus at the forefront of the avant-garde lifestyle of the inter-war years: he and his Belgian wife had simultaneous love affairs with a colorful “Bloomsberry” called Mary Hutchinson.

He dabbled in poetry during the era of T. S. Eliot and his witty, satirical novels were all the rage among the bright young things. The best of them, Crome Yellow and Antic Hay, gently mocked the Modernist movement in exactly the way that Thomas Love Peacock’s novels such as Nightmare Abbey had mocked the Romantic movement a century before.

In the fractured Thirties, he became more politically and socially engaged, though also spent several sunlit years on the French Riviera. And then, like the century itself, he was drawn forward by the magnetic power of America. He went West and became a screenwriter, best known for his work on the scripts of the Laurence Olivier Pride and Prejudice and the Orson Welles Jane Eyre. He spent his last years in Los Angeles, living in a house just below the “Hollywood” sign. This is wholly fitting, given that the Hollywood dream factory has played such a large part in turning us into the kind of people that Brave New World predicted we would become. But there is also a warning from history: in 1961, his home and nearly all his possessions were destroyed by the Bel Air fire that raged through the Hollywood canyons. One thing that Brave New World did not predict was our age of extreme heatwaves, wildfires and other catastrophic events generated by climate change.

Over the past thirty years, I have reviewed dozens of biographies and works of literary criticism. I thought it would be an interesting exercise to rewrite some of them as blog posts, stripping them of references to the books reviewed, introducing hyperlinks, and seeing if they work as capsule introductions to the authors in question. My first such attempt was on George Orwell, so this second one has to be on Aldous Huxley.

George Orwell

GEORGE ORWELL embodied the English qualities of independent thought, clarity of expression and intolerance of cant.

Over the past thirty years, I have reviewed dozens of biographies and works of literary criticism. I thought it would be an interesting exercise to rewrite some of them as blog posts, stripping them of references to the books reviewed and seeing if they work as capsule introductions to the authors in question. Here is my first such attempt, on George Orwell.

GEORGE ORWELL embodied the English qualities of independent thought, clarity of expression and intolerance of cant. As an observer of social deprivation and a rebel against Edwardian conformity, he was admired by the political left. At the same time, he wrote the definitive satire on Stalinism (Animal Farm) and one of the greatest of all novels about totalitarianism (Nineteen Eighty-Four) – which seems more prescient than ever in our age of surveillance, division and “fake news.” Remember the three slogans of the Ministry of Truth: WAR IS PEACE; FREEDOM IS SLAVERY; IGNORANCE IS STRENGTH. Perhaps most importantly for our age of technobabble, spin and jargon, he spoke through both precept and example for the virtues of clear plain prose. He reinvigorated the venerable literary genre of the essay and as both broadcaster and magazine writer represented the craft of journalism at its best. The debasement of language for the sake of political manipulation (or obfuscation) was a constant Orwellian theme, perhaps most notably in his essential essay “Politics and the English Language.”

He was a passionate Europhile, who would have loathed Brexit, but also an eloquent eulogist of England – Conservative Prime Minister John Major’s vision of warm beer, cricket on the village green and a redoubtable maiden aunt bicycling to morning communion through the mist was borrowed from Orwell.

Eric Blair – his real name – was born on June 25, 1903. His father held the modest rank of Assistant Sub-Deputy Opium Agent, 5th grade, in the Indian Civil Service, but managed to send Eric to Eton as a scholarship boy. Scholars were looked down upon by the elite and often aristocratic fee-paying pupils, but young Eric got his revenge on one of them when, in an incident curiously reminiscent of L. P. Hartley’s novel The Go-Between, together with his friend Steven Runciman (who became a distinguished Byzantine scholar), he cast a magic spell on the boy, who promptly broke his leg, then died of leukemia.

There was not enough money for university, so on leaving school Eric went to Burma and enrolled in the police force. His brief and unhappy career there gave him the material for his wonderfully perceptive essay “Shooting an Elephant” and his not especially successful first novel Burmese Days. The magazine essay – shrewdly observed, cleanly written, full of common sense – remained the literary form in which he excelled.

Back in England, he decided to become a writer, making his name with two works of reportage based on his travels among the under-class during the depressed Thirties, first Down and Out in Paris and London, then The Road to Wigan Pier. The latter was published by Victor Gollancz’s Left Book Club, but with a publisher’s preface explaining that it did not really accord with the Club’s policy of “equipping people to fight against war and Fascism” and that readers should be wary of the distinctive version of socialism propounded by the author, who was a member of “the lower-upper-middle class”.

Orwell’s uneasy relationship with the orthodox political left was further complicated by his experience fighting in the Spanish Civil War. He proved the impeccability of his anti-fascist credentials, but was shocked to witness a Soviet-backed communist purge of the Trotskyite Workers’ Party in Barcelona with which he had allied himself. His work as a war correspondent led to him being spied on by a Soviet agent fittingly called Crook.

The Soviet betrayal of the Catalan Workers’ Party was the key to Orwell’s subsequent political and literary development. It galvanized the writing of Homage to Catalonia - which many readers (including me) consider his best work - and it set him on the road to Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four, the book (published, of course, in 1948) that made his world-wide reputation and gave us such immortal ideas as Big Brother, Room 101, The Ministry of Truth, Newspeak and Airstrip One. Pulmonary tuberculosis took Orwell’s life early in 1950, less than a year after the publication of Nineteen Eighty-Four, thus depriving him of both the pleasure of Pravda’s review (“a squalid and filthy book”) and the more dubious accolade of an endorsement from J. Edgar Hoover at the FBI.

To my mind, Orwell is best understood as Rudyard Kipling’s rebellious son (think India, Englishness, beast-fable, male bonding, not very good at getting inside women): the experience of both empire and war gave them a truly global perspective (Kipling never recovered from the death of his son in the First World War, while Orwell was at his best in his anti-Nazi journalism in magazines and for the BBC during the Second). The two writers were both deeply English – Orwell was once a village shopkeeper, while Kipling found a home in Sussex where he could become a country gentleman, rooted in love of the land and respect for the traditions and knowledge of rural folk, even as his traditional belief-system smacked of ancient feudalism. At the same time, they both acknowledged that Englishness was built on the empire and yet that the traditional “island story” of the nation failed to address the barbarity of settler colonialism. As Kipling put it in his poem “The English Flag”: “I raped your richest roadstead—I plundered Singapore!” It was Kipling the globalist who in that same poem asked of parochial Little Englanders: “What should they know of England who only England know?”

Orwell, in a superb essay on Kipling, in which he condemned his great predecessor’s racism and jingoism while praising his humanity and literary art, complained that most British people did not know, or chose to ignore, how their prosperity depended on exploitation of what we now call the Global South (forgive him for his use of a term that is now a racial slur):

Because he identifies himself with the official class, he does possess one thing which “enlightened” people seldom or never possess, and that is a sense of responsibility. The middle-class Left hate him for this quite as much as for his cruelty and vulgarity. All left-wing parties in the highly industrialized countries are at bottom a sham, because they make it their business to fight against something which they do not really wish to destroy. They have internationalist aims, and at the same time they struggle to keep up a standard of life with which those aims are incompatible. We all live by robbing Asiatic coolies, and those of us who are “enlightened” all maintain that those coolies ought to be set free; but our standard of living, and hence our “enlightenment”, demands that the robbery shall continue. A humanitarian is always a hypocrite, and Kipling’s understanding of this is perhaps the central secret of his power to create telling phrases. It would be difficult to hit off the one-eyed pacifism of the English in fewer words than in the phrase, “making mock of uniforms that guard you while you sleep”. It is true that Kipling does not understand the economic aspect of the relationship between the highbrow and the blimp. He does not see that the map is painted red chiefly in order that the coolie may be exploited. Instead of the coolie he sees the Indian Civil Servant; but even on that plane his grasp of function, of who protects whom, is very sound. He sees clearly that men can only be highly civilized while other men, inevitably less civilized, are there to guard and feed them.

George Orwell is buried in the parish churchyard of an ancient southern English village called Sutton Courtenay. On one side of him is the grave of Herbert Asquith, British Prime Minister from 1908 to 1916. On the other is the plot of a family of local gypsies: an Edwardian liberal grandee on one side, travelers and hop-pickers on the other. There could be no more fitting place of rest.